In a new energy vehicle, the traction motor does not live at rated speed. A large share of real driving time sits in the low-speed region: pulling away from a stop, creeping in traffic, hill starts, low-speed torque filling, and repeated regenerative events. That reality changes what “efficiency” means. It also changes what should be sized first: current paths, inverter limits, and thermal headroom.

If you care about stable city-duty performance, repeatable launch torque, and predictable regen feel, low-speed operation is where the PMSM system earns or loses its advantage.

Low Speed Is Not Low Work

Low speed often arrives together with high torque demand.

At the wheel, launch torque can be non-negotiable, especially in scenarios dominated by low-speed torque. Upstream, that means the motor is asked to produce high electromagnetic torque while electrical frequency is still low. In practical terms, the system sees:

- High phase current even though RPM is low

- Strong dependence on control (current allocation in the d–q frame)

- Less help from speed-related voltage terms (back-EMF is lower at lower speed)

So low speed is not a relaxed operating point. It is frequently a high-current operating point.

The Real Reason Low Speed Dominates Efficiency: Current-Squared Losses

When speed rises, many PMSM losses shift toward iron loss behavior and switching-related effects. At low speed, the main limiter is usually simpler:

Copper loss dominates.

Copper loss scales with current squared. That matters because traction torque in the low-speed region is heavily current-driven:

- More torque → more current

- More current → much more heat (not linearly, but squared)

This is why two systems with similar rated numbers can behave very differently in stop-and-go driving. If one system needs higher RMS current for the same delivered wheel torque, it will run hotter and waste more energy in the exact region where you spend most of your time.

What Actually Makes a PMSM Strong at Low Speed

At low speed, a good PMSM system is not defined by one headline number. It is defined by how consistently it can produce torque with minimal extra current, minimal ripple, and controlled temperature rise.

Torque per amp under real limits

A motor may look excellent on paper, but if your inverter current limit is reached early, the vehicle will feel flat in launch or hill hold. A stronger low-speed solution keeps useful torque available before current saturation becomes the bottleneck.

Control quality at low electrical frequency

Low-speed operation magnifies control imperfections:

- Small current-regulation errors raise RMS current

- Torque ripple becomes more noticeable

- Noise and vibration become harder to hide

A well-tuned field-oriented strategy keeps torque stable while limiting unnecessary current and heat buildup.

Thermal path, not just a thermal rating

Low speed can be deceptive. Vehicle speed is low, airflow is low, and the system may spend long time near high current during creeping or repeated launch events. That creates thermal accumulation.

A system that survives a short dyno pull can still drift into derate in real traffic if the thermal path is weak or thermal margins are tight.

Low-Speed PMSM Behavior Is a System Problem, Not a Motor-Only Problem

A low-speed PMSM motor is never alone. Low-speed performance and efficiency are shaped by the entire drive chain:

- Inverter current capability (continuous vs peak, and how it behaves as temperature rises)

- DC bus voltage behavior under load and during regen

- Cable and busbar losses at sustained high current

- Cooling architecture (motor and inverter as one thermal system)

In an EV context, you only keep low-speed efficiency if the surrounding system is sized so the control strategy can deliver torque without simply pushing amps to meet demand.

A Practical Low-Speed Checklist for PMSM Design Decisions

You do not need external attachments to pressure-test a low-speed design. You can validate the logic with system questions that stay purely engineering-based:

Current and torque

- What wheel torque is required at launch and grade start?

- What phase current is needed to hold that torque continuously (not just peak)?

Thermal headroom

- How long can the motor and inverter hold high current before derate?

- How does temperature rise behave in repeated low-speed cycles?

Control stability

- Is torque ripple controlled at low electrical frequency?

- Does regen remain stable at low speed, or does it become inconsistent?

Efficiency where it matters

- What is the energy cost of low-speed segments in the duty cycle you actually face?

- Does efficiency remain stable as load moves across real operating bands rather than one test point?

Quick Table: Why Low Speed Creates Hidden Losses

| What changes at low speed | What you see in the system | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical frequency drops | Back-EMF contribution falls | More torque relies on current |

| Torque demand stays high | Phase current rises | Copper loss rises sharply (I²R) |

| Vehicle speed is low | Cooling airflow is limited | Heat accumulates faster |

| Control imperfections become visible | Ripple, noise, unstable regen | Extra RMS current and fatigue risk |

Where ENNENG Fits in PMSM Drive Solutions for Working NEVs

ENNENG focuses on permanent magnet motor development and application-oriented drive solutions. In working NEV platforms where low-speed torque and thermal stability matter, a practical approach is to treat the motor and its drive system as one package: torque delivery, current limits, cooling strategy, and control stability are evaluated together so the system behaves predictably in real duty cycles, not just at a single operating point.

FAQ

Q1: Why does a PMSM often operate at high current during low-speed driving?

At low speed, electrical frequency and back-EMF are limited, so torque production relies mainly on stator current. When the vehicle demands launch or climbing torque, current rises even though motor speed remains low.

Q2: Does low-speed operation create more thermal stress than high-speed operation?

It can. Low-speed operation often combines high current with reduced cooling airflow and longer dwell time. This allows heat to accumulate, making thermal behavior more critical than short high-speed events.

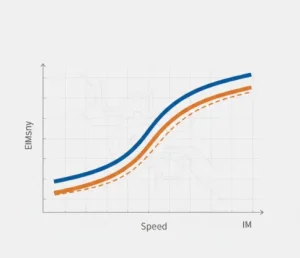

Q3: Can rated motor efficiency predict real efficiency at low speed?

Not reliably. Rated efficiency reflects specific test points. Low-speed efficiency is shaped by torque per amp, RMS current behavior, and how losses build up over time under real driving conditions.

Q4: Why is control quality more visible at low speed?

At low electrical frequency, small control deviations increase torque ripple and RMS current. This makes inefficiencies, vibration, and thermal stress easier to expose than at higher speeds.

Q5: How should low-speed behavior influence PMSM system design decisions?

Low-speed operation should guide current limits, inverter sizing, and cooling margins. Systems designed only around peak power can struggle in repeated launch, creep, and regenerative scenarios.